Teaching children with Down syndrome to use longer sentences

Learning language is more difficult for children with Down syndrome and they progress more slowly than typically developing children. Learning grammar seems to be particularly difficult and progress with grammar is usually more delayed than progress with learning vocabulary. Providing additional, targeted support to teach grammar is important in order to help young people with Down syndrome communicate more effectively and participate more fully in their communities.

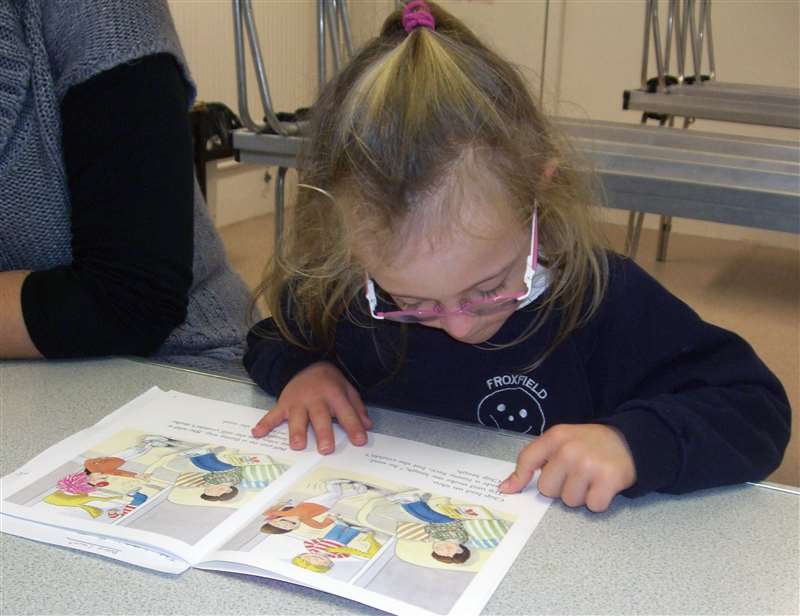

See and Learn Sentences 1 provides a structured approach to help children with Down syndrome improve their understanding of grammar and to use longer sentences. It combines explicit vocabulary teaching with book reading and uses printed words to provide a visual representation of vocabulary, grammar rules and sentence structures - aiming to overcome some of the challenges usually experienced by children with Down syndrome when learning language.

Here, we summarise the research that informs this approach to teaching grammar and longer sentences. Further information about speech, language and literacy development for children with Down syndrome is available on the See and Learn website.

Learning about grammar and speaking in sentences

Joining words together

Children develop their language because they want to communicate and tell you things. At first, they use single words so they can tell you one item of information at a time such as "car", or "more", or "sleep". Next, they begin to join two keywords together to express two items of information such as "big car", "more dinner", "dog sleep", "Kate eat". These two-keyword phrases usually combine nouns and verbs, or nouns and adjectives. They then use three keyword sentences to communicate even more information such as "big car gone", "mummy more dinner", "dog sleep chair", "Kate eat apple". They may also use four keyword sentences such as "dog chasing big cat" or "Kate go school car".[1,2]

There is a link between the number of keywords combined and a child's vocabulary size. Children, including those with Down syndrome, begin to join two keywords when they say or sign at least 50 words. They will understand two-keyword phrases before they use them. They begin to learn some grammatical markers such as the possessive 's for 'mummy's car' and the -ing form of the verb at this two keyword stage.[1,2]

Learning the grammar rules

At first children use three and four keyword 'sentences' without the joining function words which make the sentences grammatically correct (for example, “dog chasing big cat” rather than "that dog is chasing a big cat"). The correct use of function words such as articles/determiners (a, the, that) auxiliary verbs (is, are, can, has, do, will), pronouns (he, she, they, him, her, them) prepositions (in, on, to, under) is governed by rules.

For example, we say "Kate is going to school" but "the children are going to school" (is for singular, are for plural subjects in the sentence). We use tense markers to identify when something happens ("I am going to jump", "I am jumping", "I have jumped").[1,2]

Word order rules

Children also need to learn that a change in word order changes meaning. For example, "Has Daddy gone?" is a question, "Daddy has gone" is a statement. "Kate is chasing Mary" does not have the same meaning as "Mary is chasing Kate".

It takes several years (from 2 years of age to 5 or 6 years of age for typically developing children) to master the most common rules of grammar used in their language, with considerable individual differences among all children. Children usually learn the common rules from listening to how those around them use language. The use of some more complex grammar and sentence structures is more common in written than spoken language and so will be mastered during school years and influenced by being able to read. Children learn the rules for sentences and grammar in a predictable order.[1,2]

Children, including those with Down syndrome, do not begin to use most function words or tense markers in their spoken sentences until they have at least 200 to 300 words in their spoken vocabulary though they may understand them much earlier.[3-6] However, they will be joining three and four keywords without the function words or grammatical markers when they have smaller vocabularies (100-200 words, with large individual differences). Because vocabulary size is linked to sentences and grammar development it is important to keep teaching new words while also encouraging longer phrases and sentences.

The challenges for children with Down syndrome

Children with Down syndrome show an uneven profile when learning to talk. There are four components to develop when learning to talk, communication, learning vocabulary, learning grammar and developing clear speech. Children with Down syndrome usually want to communicate and persist in getting their message across using words and signs. They are slower to develop their vocabulary but continue to do so steadily so that by teenage years their vocabulary progress is ahead of their grammar progress. Most children with Down syndrome struggle to develop clear speech production. This leads to their communication and vocabulary skills being seen as relative strengths but grammar and speech development as relative weaknesses.[7-9]

Most children with Down syndrome seem to find mastering grammar difficult and continue to use keyword or telegraphic sentences to get their meaning across when talking. They tend to omit function words and word endings when speaking (often omitting articles, prepositions, forms of verbs and auxiliary "be", verb past tense -ed, third person singular -s, noun plurals). Children with Down syndrome used fewer modal auxiliaries (e.g. 'can, may, will') and lexical verbs (e.g. main verbs other than have, do, be) when compared with typically developing children matched for the length of their utterances.[7] While research studies suggest that their use of grammar when talking is delayed relative to their non-verbal mental age, their understanding of grammar may be as expected for mental age and does slowly improve during school years for many children.

Several reasons have been suggested by researchers for the delays in mastering and using grammar seen among children with Down syndrome: [6-10]

- Difficulties hearing some function words and word endings - The function words such as is, are, the, a, and the word endings (-s, -ed, -ing) are not stressed in sentences as we talk which means they may be more difficult to hear and learn. This difficulty will be increased for the many children with Down syndrome who have a hearing loss.[10]

- Difficulties processing longer sentences - The children's limited verbal short-term memory will also be making it difficult to hold and process longer sentences when they hear them.

- Difficulties comprehending the meanings of some words - The function words may not add anything obvious to meaning as we can see if we compare "he go school" and "he is going to school". The use of these function words may have to be learned with repeated practice.

- Difficulties saying longer sentences clearly - The children's speech production difficulties mean that saying longer sentences clearly enough to be understood is a challenge. It has been suggested that the children may learn that they are more likely to be understood if they use two or three keywords and do not try to say all of the words in a sentence. Their speech difficulties may also mean that producing the grammatical markers, which are often word endings, is too difficult.

- Difficulties learning grammar rules implicitly - Most typically developing children learn many of the basic grammar rules from exposure to spoken language and from their desire to use language to communicate - without explicit instruction. Children with Down syndrome may find learning in this way more difficult. They may need more opportunities to see and practice examples of sentence structures and rules.

Despite these challenges, research studies do suggest that children with Down syndrome learn to build sentences and learn early grammar rules in the same order as other children.[6-9]

Intervention strategies

There is very little research on teaching grammar to children with Down syndrome available. The few published studies have worked with teenagers, but do suggest that grammar teaching can be effective.[11-14]

Experts in language development for children with Down syndrome suggest that beneficial teaching approaches may include:[7]

- repeated opportunities to hear spoken words and sentences

- visual supports to communicate meaning and help the children to recall information

- repeated brief and simple instructions

- tasks that are broken down into small steps

- encouragement to ask for forgotten information

- visual teaching materials such as storybooks

Other evidence-based methods used to teach grammar to other language delayed children, include:[15]

- encouraging imitation

- practicing specific sentences structures or grammar rules

The design of See and Learn Sentences 1

The teaching strategies adopted by See and Learn Sentences 1 are informed by the available evidence and by extensive experience supporting children with Down syndrome. These include:

- Explicitly teaching new, developmentally appropriate vocabulary - Children need to learn the meanings of many spoken words to communicate. The number of words children can say determines the length of sentences they start to use. We teach new vocabulary by introducing new words in simple books and by playing matching, selecting and naming games with picture cards. We have selected developmentally appropriate vocabulary, consistent with the available evidence of word learning among English-speaking infants and children.

- Grouping new vocabulary by themes or categories - Teaching vocabulary in sets of words that are conceptually linked can help to develop children's understanding. We introduce vocabulary in books that group words together by themes or categories. We practice matching, selecting and naming activities with vocabulary in these groups.

- Making language visual - We introduce vocabulary, sentence structures and grammar rules in written sentences. Here, the children can see words and word endings they may miss when listening to spoken sentences - and we can point to them. The children can also reread words and do not have to rely on verbal short term memory to hold the whole spoken sentence to extract meaning. This may help alleviate some of the specific difficulties experienced by children with Down syndrome when learning language.

- Teaching whole word reading - We teach new written words with whole word matching, selecting and reading activities. We use a word to picture matching activity to both test the children's understanding of written words and to emphasise the links between words and their meanings. At this stage, we focus on teaching new words as whole sight words (where possible selected from vocabulary we have already established the child understands).

- Teaching carrier phrases - When introducing new vocabulary we often take the opportunity to explicitly teach carrier phrases - including "This is ...", "I am ...", "Look at ...". These can be helpful for encouraging children to use longer phrases and sentences when communicating.

- Modelling sentence structures and grammar rules - We model structures and rules by repeating common patterns and by contrasting specific rules. For example, the Girls and boys book introduces the plural -s rule and the is for singular / are for plural rule with repetition and contrasts singular/plural structures on facing pages.

- Teaching in small steps - To reduce demands on working memory, and to simplify learning activities, we use simple, short activities to introduce, teach and test the understanding of new vocabulary, written words and sentences. The basic activities (matching, selecting, naming) are first learned with pictures when teaching vocabulary, and then used again with written words to teach sight words and sentences.

- Offering lots of opportunities for rehearsal and consolidation - We reuse previously learned words and repeat previously taught sentence structures and grammar rules in later books to provide opportunities for practice and to consolidate learning. Most children with Down syndrome will require substantially more repetition than typically developing children to learn and retain new knowledge.

References

- Clark, E. (2009) Chapter 5 Sounds in Production in E. Clark. First Language Acquisition (2nd edition) Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Hoff, E. (2014) Language development. (5th Edition) Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

- Galeote, M., Sebastián, E., Checa, E., Rey, R., & Soto, P. (2011). The development of vocabulary in Spanish children with Down syndrome: Comprehension, production, and gestures. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 36(3), 184-196.

- Checa, E., Galeote, M., Soto, P. (2016) The Composition of Early Vocabulary in Spanish Children with Down Syndrome and Their Peers With Typical Development. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 25, 605-619.

- Galeote, M., Checa, E., Sebsatian E., Robles-Bello, M. (2018) The acquisition of different classes of words in Spanish children with Down syndrome. Journal of Communication Disorders, 75, 57-71.

- Galeote, M., Soto, P., Sebastián, E., Checa, E., & Sánchez-Palacios, C. (2014). Early grammatical development in Spanish children with Down syndrome. Journal of Child Language, 41, 111-31.

- Roberts, J.E., Chapman R.S., Martin, G.E. & Maskowitz, L. (2008) Language of preschool and school age children with Down syndrome and Fragile X syndrome. In Roberts, J.E., Chapman R.S. & Warren, S.F. (Eds.) (2008) Speech and Language Development and Intervention in Down Syndrome and Fragile X Syndrome. (pp 77-116) Baltimore, MD: Paul Brookes Publishing Co.

- Abbeduto, L., Warren, S. F., & Conners, F. A. (2007). Language Development in Down Syndrome: from the Prelinguistic Period to the Acquisition of Literacy. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 13(3), 247-261.

- Martin, G, Klusek, J, Estigarribia, B, J, R. (2009). Language Characteristics of Individuals With Down Syndrome. Topics in Language Disorders, 29(2), 112-132.

- Laws, G., & Hall, A. (2014). Early hearing loss and language abilities in children with Down syndrome. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 49(3), 333-342.

- Buckley, S.J. (1993). Developing the speech and language skills of teenagers with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome: Research and Practice. 1(2) 63-71.

- Buckley, S. (1995) Improving the expressive language skills of teenagers with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice, 3(3), 110-115.

- Sepulveda, E.M., Lopez-Villasenor, L.M. & Heinze, E.G. (2013) Can individuals with Down syndrome improve their grammar? International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 48, 343-349.

- Baxter, R., Rees, R. & Perovic, A. Hulme, C., (2021) The nature and causes of children’s grammatical difficulties: Evidence from an intervention to improve past tense marking in children with Down syndrome. Developmental Science 25.4 https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.13220

- Ebbels, S., (2014) Effectiveness of intervention for grammar in school-aged children with primary language impairments: A review of the evidence. Child Language Teaching and Therapy (30) 7-40.